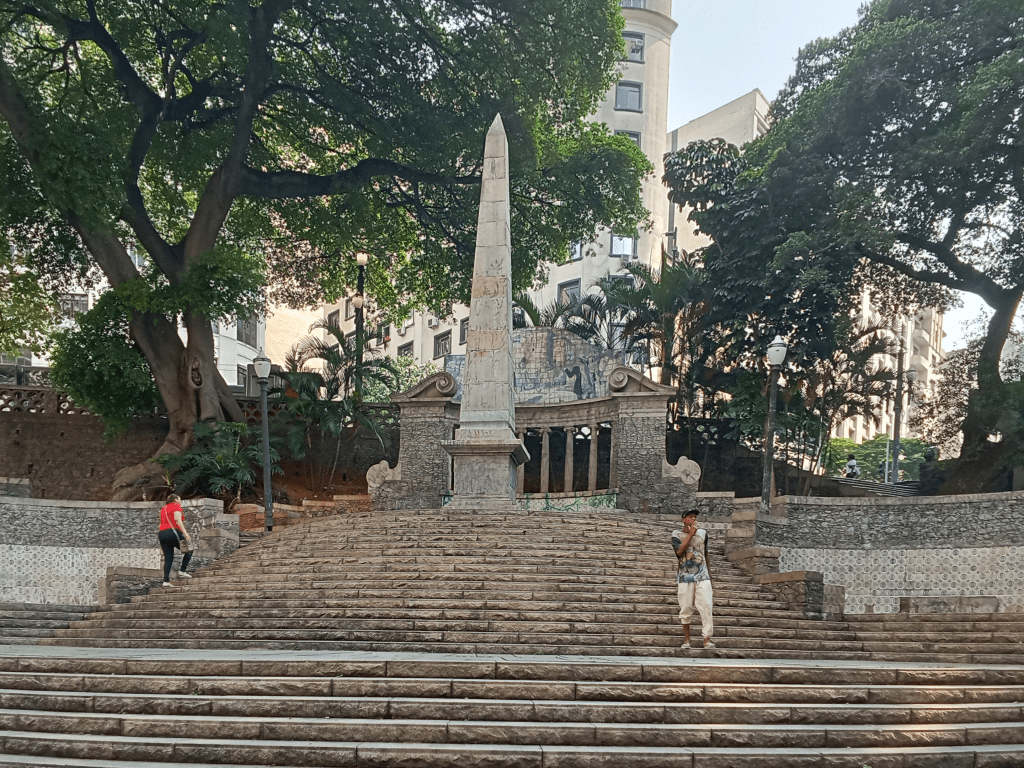

According to a project by engineer Daniel Muller, the Piques obelisk and fountain was built in 1814, on the outskirts of the city, at the place where the road leading to or from the interior began. The text “to the zeal of the public good” affixed to the monument expressed the intentions of the triumvirate that ran the city in highlighting the importance of the work on the canal that brought water from the Reúno tank for the well-being of São Paulo. Taking advantage of the slope of the land, the water from the obelisk tank fed, a little further down, the fountain that served both travelers and residents in an intervention similar to the two obelisks erected by the viceroy of Brazil, near the alligator fountain of the public promenade in Rio de Janeiro, in 1806.

In 1919, the mayor Washington Luís asked the architect Victor Dubugras to develop a recovery project for Largo do Piques, which, with the progressive establishment of the railway network, had lost its strategic importance for the movement of people and goods. With a good sense of scenography, the architect of French origin, trained in Argentina, created a surrounding area of semicircular stairs, topped by a portico of Ionic columns that served as a majestic backdrop for an elliptical tank.

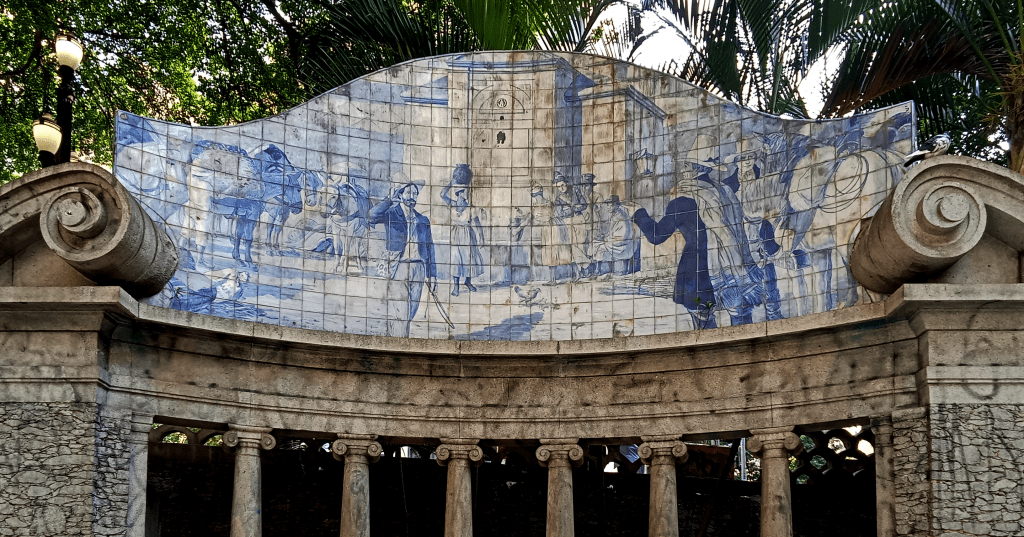

The collaboration of the painter José Wasth Rodrigues (1891-1957), who designed the blue and white tiles on the pediment and also the tiles with the city’s coat of arms that decorate the bench area, added a clear neocolonial reference to the Memória Square project. Adopting this approach, in the years immediately following, the same partnership would create the six monuments commemorating the centenary of Independence which would be built on the old Serra do Mar Road.

In the tile panel, the painter, who had been encouraged by Monteiro Lobato to create a new style based on traditional values and had collaborated with the engineer and archaeologist Ricardo Severo in recording Portuguese-Brazilian architectural elements, depicted a scene of customs that took place around the old Piques fountain. With meticulous care, José Wasth recreated the costumes of the muleteers, soldiers, slaves and citizens of São Paulo.

For the republicans, the program of creating Brazilian art was the only way to guarantee national cohesion and, at the same time, the sure path to future progress, as the architect Severo succinctly argued in his lecture at the Sociedade de Cultura Artística, held on July 20, 1914:

The epics of humanity are based on the mysterious legends of old times; these antiquated rhapsodies that people enthusiastically sing in their triumphant advance towards that unknown future, even more distant, and increasingly so, than that distant past of barbaric origins. These legends, beliefs and myths have formed the links of the sentimental chain that fraternally unites men and peoples to create the homeland.

Since it was believed that society would progressively evolve and that art was responsible for maintaining national cohesion – something that religion could no longer do and politics alone was incapable of doing – it was necessary to denounce the error of revivalisms based on the style and history of foreign peoples.

In 1920, the still young writer Mário de Andrade, after a long-planned visit to Minas Gerais, also welcomed with moderate optimism, in articles published in the Revista do Brasil, the recreation of a traditional architecture, modelled on Portuguese-Brazilian baroque models, and, in particular, the work of the Polish architect Georg Przyrembel, who would participate prominently in the Modern Art Week of 1922:

Finally, we would like to make a special reference to Mr. Pzirembel’s project, currently under construction, for the future chapel of Monserrate, in Santos. The artist knew how to draw on the traditional source [and] created a delightful project that even includes tiles, which our architects have so opportunely recovered.

As the tile panel in the new Largo da Memória demonstrated, the record of the past is only the starting point for a new and necessary national art that responds to the new demands of the present.

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANDRADE, Mário. A arte religiosa no Brasil. Edição crítica de Claudéte Kronbauer. São Paulo: Editora Experimento e Editora Giordano, 1993.

KESSEL, Carlos. “Vanguarda efêmera: arquitetura neocolonial na Semana de Arte Moderna de 1922” in Estudos Históricos, n. 30, 2002, pp. 110-128.

SEVERO, Ricardo. A arte tradicional no Brasil. A casa e o templo. São Paulo: Tipographia Levi, 1916